Thomas Merton: one of the most significant spiritual masters of the post-modern age, hailed as a contemporary “Father of the Church” – or great teacher of its treasured wisdom. It has been said that the task of theology in the 21st Century is to catch up to Merton, who anticipated all the turns taken by the Catholic community in the past century: toward the person and the mystery of human interiority and subjectivity; toward the world and the challenges of global solidarity; toward the natural world and the mystery of deep incarnation; toward “the Other” and the ubiquitous mystery of pluralism and diversity. A monk and poet, a critic of culture and politics, a reformer and social visionary, a prophet of non- violence, Merton knew the religious terrain of this planet, and vigorous explorer that he was, he likewise became a skillful orienteer within those sacred worlds he visited intellectually, interpersonally, actually. As such, one of his many challenges was the call to deep and sustained interreligious dialogue “among those of various religions who seek to penetrate the ultimate ground of their beliefs by a transformation of religious consciousness.”1 Though Merton’s religious appetite was broad and varied, Eastern spiritualities – and Buddhism in particular – were his great fascination, which led him to investigation, conversation, experimentation, visitation, integration, and finally transformation toward more expansive horizons of experiential life in the Spirit. Under these several rubrics something of Merton’s mastery of the art of sacred dialogue comes clear.

Fascination Merton’s fascination with eastern spiritualities began when he was a teenager at Oakham School in England, preparing a paper for debate on Mahatma Gandhi - an allurement which matured into his profound commitment to non-violence, and the eventual publication of Gandhi on Non- Violence in 1965. Later, at Columbia University his attraction to “Oriental mysticism” was mostly an intellectual affair, until his encounter with a Hindu monk, Bramachari who, ironically, challenged Merton to investigate the Christian mystical tradition, opening him to western as well as eastern classics. This discovery of Catholic spirituality ignited his conversion to Christ, led him to the Church, and ultimately to the Abbey of Gethsemani where he embraced monastic life as a Trappist on December 10, 1941.

Investigation Fascination with life in the Spirit soon led to serious investigation of the varieties of religious wisdom in general, and Buddhism specifically. By the early 1950’s Merton was being mentored by a host of Asian scholars, among them D.T. Suzuki who awakened Merton’s deep and abiding interest in Zen Buddhism. Fr. Doumoulin, SJ, Dr. John Wu, Professor Masao Abe, Marco Pallis and others directed his intensive studies, which gave rise to his own serious writings on Buddhism: “The Inner Experience” (begun late 1950’s), Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander (1966); Mystics and Zen Masters (1967); Zen and the Birds of Appetite (1968); and his posthumous Asian Journal (1973), among others.2

Conversation Merton was a dialogical man, ever in conversation with himself, his friends, the world, the alluring strangers of other worlds, and especially with God – even as these various dialogues were conducted in silence. Indeed, Trappist life became for Merton a way to live his “vow of conversation” with countless tribes of spiritual seekers and masters who became companions in his quest for experiential wisdom. His personal journals and volumes of correspondence attest to the staggering numbers of dialogue partners he had over his twenty-six year tenure at Gethsemani and to the seriousness and breadth of these dialogical engagements.1

Merton was convinced that communication in depth, across the lines that have divided religious traditions, is not only possible and desirable, but essential for the destinies of the 20th and now 21st century human community.3 Careful and conscientious during his many years of Buddhist / Christian conversation, Merton eventually formulated principles he considered relevant to all interreligious dialogue. First, he spoke of contemplative dialogue, implying that such engagement must be reserved for serious practioners of their spiritual traditions, disciplined by a habit of meditation, and formed by their tradition’s transformational techniques and technologies. Secondly, dialogue must be clear and authentic, going beyond facile syncretism, or vague verbiage and superficial pieties. Thirdly, dialogue requires scrupulous respect for important differences without useless debate; understanding unfolds as the capacity for true and patient listening deepens. Fourthly, attention must be concentrated on what is really essential to the sacred quest: true self-transcendence, consciousness transformation, and enlightenment. Fifthly, questions of institutional structures and other elements of form are to be seen as secondary and not become a focus of attention.4

Experimentation Merton’s engagement with Buddhism went beyond conversation, because he believed that we had finally reached a stage of long overdue religious maturity where it is possible to remain perfectly faithful to a Christian commitment and yet learn in depth from a Buddhist discipline and experience.5 Since “God is neither affirmed nor denied in Buddhism,” he began his own experiments with Zen, a trans-cultural, trans-religious, transformational practice, whose main purpose is an ontological awakening to the ultimate ground of being.6 In it he found techniques which directly addressed the crisis so obvious to him: soul-loss occasioned by the technologization and commodification of the modern person, with the consequent need – especially for westerners – to recover our interiority, spontaneity and depth in a world which has made us rigid, artificial and spiritually void.7 Merton welcomed the infusion of Zen into Christian life as a skillful means to keep alive the contemplative experience. By grounding the meditator in direct experience of reality,8 Zen promoted healing fractured, dualistic consciousness with its flight from being into verbal preconceptions and preoccupations. Alert to the challenges of spiritual evolution, Merton believed a transformational practice like Zen was essential “as we grow toward full maturity of universal man (sic)… of concern to all religions.”9

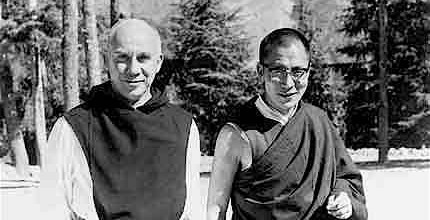

Visitation Though Trappist life restricted personal engagements with the growing cohort of Buddhist correspondents, in early 1968 the young Vietnamese monk, Thich Nhat Hanh visited Merton at his hermitage in Gethsemani – a transformative visitation for both, intensifying Merton’s resonance with Zen Buddhism. Although he believed that our real journey in life is interior, he desired an experiential immersion into the ethos and cultures that had produced an interiority he sensed Christians had lost. Later that year, Merton was allowed to go on pilgrimage to Asia, “to drink from ancient sources of monastic vision and experience…to become a better and more enlightened monk.”10 During his months of interreligious visitation in Asia, he vividly encountered the Theravadan tradition, but was particularly fascinated with the Vajrayana and Dzogchen schools of Tibetan Buddhism, with whose lamas and rinpoches he sensed an immediate resonance of “heart speaking to heart.” This was especially so with His Holiness, the Dalai Lama, who saw in Merton the real meaning of the word “Christian.” His Asian Journal is dense with reports and musings that record countless insights and revelations his numerous hosts offer their most eager student. By December 1968 he was swimming in the grace of Buddhism, discerning and distilling its particular wisdom for him, and what he might be called to next.2

Integration Sadly, it is impossible to know how Merton might have integrated the extraordinary experience of his Buddhist visitations, because on the 10th of December 1968 he died in Bangkok, Thailand while participating in one of the earliest intermonastic Buddhist Christian Hindu dialogues sponsored by the Catholic forum called Interreligious Monastic Dialogue. We know he had plans to pursue Dzogchen more intensively, to perhaps study with one of the Rinpoches he had visited, and then maybe establish a retreat center in New Mexico for the dialogue between Tibetan Buddhism and Catholicism. His imagination was full of possibilities, with the hope always to go further into the depths of spiritual experience – as a Christian – to advance his own and his tradition’s higher spiritual evolution. In a dream a month before his death he sees himself back at Gethsemani but “dressed in a Buddhist monk’s habit” – both Tibetan and Zen.

Transformation Reading the reports of his fellow-travelers11, it becomes uncannily clear that several of his more clairvoyant Buddhist hosts witnessed in Merton a man on the verge of a great transformation – even of death. As if in ritual premonition, several days before his accidental electrocution in Bangkok, Merton was on visitation not to any Buddhist master, but to the Buddha himself at Polonnaruwa, before whose monumental, silent reclining stone sculpture he would experience his ultimate transformational awakening. As Merton stood before the statue of the dying Buddha the desire of all his Asian explorations became clear; the whole affair was settled in a flash, and he realizes that “everything is emptiness and everything is compassion.”12 As with much of the life of this great spiritual master, his death is also instructive, even revelatory. It marks the climax of fascination, investigation, conversation, experimentation, visitation, and integration of Buddhist wisdom and methodology experienced as compliment to and application of his years of practicing Christian kenosis, of laboring to put on the mind of Christ, and thereby recover his true self, his paradisal nature. In all this he showed us a way to greater spiritual maturity, coursing an evolutionary trajectory by finding wisdom vehicles in all the world’s religions. And then disembarking, he made by walking, a path of awakening to a consciousness, beyond all religious forms, that can behold always and everywhere, that – in truth – “everything is emptiness and everything is compassion.”

Kathleen Deignan, CND

Footnotes

^1 See Merton’s “Monastic Experience and East-West Dialogue,” The Asian Journal of Thomas Merton, ed. Naomi Stone, Patrick Hart and James Laughlin (New York: New Directions) 309 ff.

^2 For a comprehensive bibliography of Merton’s works and illuminating essays on the themes and issues of his literary corpus see The Thomas Merton Encyclopedia, edited by William Shannon, Christine Bochen and Patrick O’Connell (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books 2002).

^3 “Monastic Experience and East-West Dialogue,” op cit. 313.

^4 Ibid. 316-317.

^5 Ibid. 313.

^6 Mystics and Zen Masters (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1967), 282; Zen and the Birds of Appetite (New York: New Directions, 1968) 4.

^7 The Way of Chuang Tzu (New York: New Directions) 16.

^8 Zen and the Birds of Appetite, op cit. p. 44.

^9 “Monastic Experience and East West Dialogue,” op cit 316-317.

^10 The Asian Journal, op cit 312-213.

^11 See Merton and Buddhism: Wisdom, Emptiness and Everyday Mind, ed. Bonnie Thursdon (Louisville, KY: Fons Vitae) 15-90.

^12 The Asian Journal, op cit 235.

Leave a Reply